5 Reasons To Full Squat

The full squat is one of the most basic and fundamental human postures. Due to industrialized society’s heavy reliance on chairs and modern footwear however, it has become a position that many people have difficulty achieving.

Born to Squat

The full or deep squat refers to a position where the knees are flexed to the point that the back of the thighs rest against the calves with the heels remaining flat on the floor. Young children under the age of four will instinctively go into a deep squat when they want to reach for something low, and often hold themselves in a stable squatting position to engage in play.

Among Asian adults, squatting often replaces sitting.1 So what happens to Westerners, as we grow into adults, that causes us to lose this ability? This is primarily a case of use it or lose it. Many cultures throughout history would rely on the squatting posture as a means of performing work, eating meals, or resting. Modern society has all but eliminated the need to squat in our daily lives.

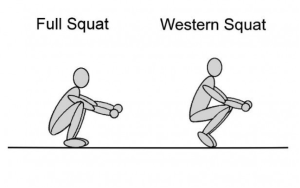

A second reason relates to the design of modern footwear that often features an elevated or raised heel. Habitual shoe wearing causes a shortening of the calf muscles and Achilles tendon, and a gradual loss of the ankle mobility required to properly do a squat. This often leads people to perform a variation called the Western squat, where the heels remain propped up in the air.

Fortunately, many of the adverse effects brought on from frequent sitting, improper footwear, and squat avoidance are reversible. When performed correctly, the full squat carries many benefits for physical health. Squatting can be performed as a body weight exercise, to reach something on the ground, or simply as a rest position.

5 Health Benefits of the Full Squat

- Ankle Mobility

Limited ankle dorsiflexion range of motion is a common problem linked to a number of other issues in the body, including overpronation, bad posture, and runner’s knee. A loss of ankle mobility is caused by both inflexibility in the calf muscles and Achilles tendon, and stiffness in the joint. A proper squat, with the heels flat on the floor, requires good flexibility at the ankle. Getting into and maintaining a full squat is a great way to improve ankle mobility and restore full range of motion.

- Back Pain Relief

Many people have an excessive curvature in their low back as a result of the pelvis being pulled down in the front by tight hip flexor muscles. During a full depth squat the pelvis rotates backward, allowing the spine to elongate. This stretches the tight or shortened muscles in the low back. The body’s position in a deep squat also produces a traction effect that decompresses the spine by creating space between the individual segments of the back.

- Hip Strengthening

In a person whose hip muscles are weak, you’ll often see their legs move inward (adduct) and internally rotate when they perform closed-chain movements, like jumping or going down stairs. This adducted, internally rotated position puts the knee at an awkward angle and can lead to injuries. A full squat moves the hips in the opposite position, abduction and external rotation. The squat strengthens the muscle groups responsible for performing these actions, allowing them to better control the position of the entire leg.

- Glute Strengthening

The gluteus maximus is one of the largest muscles in the body, and with good reason. The muscle comprises the bulk of the buttock region and is integral to performing many activities we do on a daily basis like walking, lifting, and running. The glute max is also an important stabilizer muscle of the trunk and leg. EMG studies have shown that during a squat the glute muscles become targeted only after descending past the half way point.2 This means the same strengthening benefit cannot be achieved from only squatting in a partial range of motion. Coming in and out of a deep squat is by far one of the most effective ways to strengthen the glutes. Not many people are going to complain about having a firmer backside.

- Posture Correction

The cumulative effect of working on the areas listed above is an overall improvement in both static and dynamic posture. When joint mobility and lower body strength are restored the entire musculo-skeletal system will naturally be able to assume better alignment, which has a tremendous impact on the way we look, feel, and move. The full squat is a way to reverse some of the bad habits the body has assembled from our modern lifestyle.

The Modern Squat

When a person not used to performing a full squat attempts to squat down, often times their heels will lift off the floor, or they will fall backwards. These are two signs of a loss of ankle flexibility. We show you already a picture demonstrating the difference between a full depth squat and the Westernized squat that occurs when the ankles are stiff.

Notice how in the Western squat the ankle remains at about a 90 degree angle. Without adequate ankle mobility, attempting to go any lower would move the center of gravity behind the base of support, and the person would lose their balance and tip over backward. The disadvantages of remaining up on the toes include:

- a higher center of gravity and smaller base of support (the toes), making this a less stable position.

- an overuse of the calf muscles to stay in the position, making it unsuitable for resting

- increased compression of the soft tissue between the upper and lower leg

Many adults instinctively go into the Western squat because it has become physically impossible for them to get their heels down. Correctly performing a full depth squat is a sign of good mobility and strength and can be a reasonable goal for anyone looking to improve their fitness.

Preparing to Squat

Since the squat is such a basic and functional movement, simply practicing getting into the position is often all that is needed to achieve proper form. For anyone unfamiliar with the squatting movement it would be wise to work on the smaller components first, to build up the necessary strength and motor control needed to get in and out of the position. Here is an article and video showing the fundamentals of good squatting technique and providing some recommendation on ways to progress for beginners.

For someone who finds they have the strength to squat down but then have difficulty getting their heels flat without losing their balance it might be necessary to do some extra calf and ankle stretching to gain flexibility. Here is an article that goes over some helpful ways to increase ankle dorsiflexion.

Are Squats Bad for Your Knees?

Some people may have heard advice that performing a full squat is dangerous or bad for the knees. Squatting like most exercises carries a certain degree of risk, but the notion that squats hurt the knees is largely a myth.

When performed properly the risks are greatly reduced and usually outweighed by the benefits that can be gained from regular squatting.

Based on current evidence, full range of motion squatting using your own body weight is not only a safe activity, but one that can have a great influence on overall physical health. Still, it is important to be aware of the risks to lower any potential for injury before performing any movement the body is not accustomed to doing. The two major concerns usually voiced over squatting are the potential for joint wear leading to arthritis and ligament injuries.

Squats may actually decrease the risk of arthritis

During a squat there are increased comprehensiveness forces on the joints of the knee. Very few studies however have shown that squatting can cause damage to the joint. One retrospective study on a group of elderly subjects in Beijing found that those who reported squatting several hours a day in their youth were more likely to demonstrate osteoarthritis of the tibiofemoral (TF) joint.3 A later study however found that squatting actually decreased the risk of TF arthritis when performed at least 30 minutes a day.4

The reason for these contradictory findings is not clear. The important thing to remember is that, as is true for most activities, moderation is key. The body is certainly capable of adapting to a natural squatting position, and almost all of us were able to do it at some point in our lives.

The other joint in the knee subject to increased loads during squatting is the patellofemoral (PF) articulation, between the underside of the knee cap and the femur. The compressive forces at the PF joint increase as the knee moves into flexion (depth of squat). However, during that time the contact surface of the joint also increases.5 The increase in contact area distributes the joint forces over a larger surface area, which maintains, or even reduces, joint stress as you get deeper in your squat. Patellofemoral compression force should still be a consideration though for anyone with a history of anterior knee problems or cartilage damage of the patellofemoral joint.

In regards to ligament injuries, the idea the deep squatting when performed as a weightlifting exercise causes ligament laxity in the knee can be traced back to an older study performed in the 1960s. Later studies have refuting these results and actually found that squatting enhances knee stability.6,7

The same principles that apply to other forms of exercise also apply for squats. Squatting too often, holding the position for hours on end, or not allowing your body to recover between squatting session can place you at risk for injury.

Summary

The full squat is a natural human posture often used as an alternative to sitting in Asian cultures and among young children, but rarely performed by adults in Westernized countries. Spending time in a squat position offers many health benefits and can serve as way to correct postural imbalances. Squatting is a safe activity when performed properly. Someone who is healthy and in relatively good physical shape without a history of knee injuries should be able to squat safely with minimal risk. Individuals with a history of knee injury need to give consideration to the increased forces placed on the structures of the knee when squatting. A lack of ankle mobility is usually the limiting factor that would prevent an individual from reaching full depth. The ability to do a full depth squat is a sign of good physical health.

References

- Dobrzynski J. “An Eye on China’s Not So Rich and Famous”. The New York Times. Retrieved Sep 23 2012.

- Caterisano A, Moss RF, Pellinger TK, Woodruff K, Lewis VC, Booth W, Khadra T. The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles. J Strength Cond Res. 2002 Aug;16(3):428-32.

- Liu CM, Xu L. Retrospective study of squatting with prevalence of knee osteoarthritis. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2007 Feb;28(2):177-9.

- Lin J, Li R, Kang X, Li H. Risk factors for radiographic tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis: the wuchuan osteoarthritis study. Int J Rheumatol. 2010;2010:385826.

- Besier TF, Draper CE, Gold GE, Beaupré GS, Delp SL. Patellofemoral joint contact area increases with knee flexion and weight-bearing. J Orthop Res. 2005 Mar;23(2):345-50.

- Chandler T, Wilson G, Stone M. The effect of the squat exercise on knee stability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 21(3). Pp 299-303. 1989.

- Escamilla RF. Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Jan;33(1):127-41.

Sitting And Tight Hip Flexors

December 12, 2012 by James Speck Leave a Comment

Tight hip flexor muscles are often implicated as the cause of a number of problems in the body. Most notably tight hips get blamed for low back pain and bad posture, but the association has also been made with several different running-related injuries and even poor athletic performance. Sitting for prolonged periods is probably the most popular theory of how the hip flexors might tighten, as sitting can hold the muscles that cross the front of the hip in a shortened position.

There has been a lot of news recently about the health perils related to sitting, although scientists still haven’t been able to explain what makes extending bouts of sitting harmful. Similarly, as pointed out by health writer Todd Hargrove in this post, there is not a lot of evidence in favor of the claim that sitting actually causes the hip flexors to tighten up either.

Effect of Sitting on Hip Flexors

Sitting places the muscles crossing the hip into a shortened position, but even a full day of sitting would not seem like enough time to cause a permanent change in the tissue, as long as at the end of the day we get up and walk around a little. The shortening of a muscle or other tissue after prolonged immobilization, called a contracture, does happen, but usually requires a great deal more than just a long day spent typing in front of the computer occur. Still, could there be some validity behind the idea that sitting can effect the hips?

Why Muscles Get Tight

Biomechanical

Muscle inflexibility is a complicated topic involving both cellular biology and the nervous system. There is evidence that adaptive shortening can occur in muscles by way of the body reducing the number of sarcomeres present in the muscle tissue. This process would be analogous to removing links in a chain. Whether or not this shortening can occur from prolonged periods of sitting is a good question that hasn’t yet been answered. There is some research that suggests muscle length can be preserved by intermittent periods of stretching but it’s not clear if this would apply to office workers sitting at their desks day after day over a period of months or years.

Neuroscience

The neurological component of stiffness deal with the body sending signals to the muscle to resist passive stretching, even when there has been no change in the physical length of the tissue. This type of inflexibility of the hip flexors might be a protective response of the nervous system in response to something else going on that the body perceives as a threat (e.g. increased forces on the low back or joint instability).

Muscle Imbalances

Our muscles and joints do a very good job at adapting themselves to the positions we put them in on a regular basis, so frequent sitting may predispose the hips to assume a flexed position. It would seem that if sitting were to result in a loss of hip extension however, this would also require us to stop, or at least considerably reduce, any activity that requires hip extension. Hargrove summed this up nicely from the comment section of the article cited above:

I definitely think sitting in a chair too much is bad news, just not for the reason that it structurally shortens tissues. The big problem with sitting in a chair IMO is that it displaces other activities which are necessary for maintaining proper movement patterns and tissue length […]

There are only a handful of activities where hip extension, and consequently, good hip flexor extensibility is required. Sprinting and lunges are probably the two most common, and how often do most people do these movements? Interestingly enough, one of the leading theories about the harmful effects of sitting on general health centers around the lack of use of the large muscles in the legs that occurs when we sit.

Relative muscle strength and activity may also be a factor in any muscle shortening related to sitting. Individuals with above knee amputations develop hip flexion contractures because the hip extension torque producing ability of the gluteus maximus is impaired while strong hip flexors, like the iliopsoas muscle group, are left intact. Similar contractures are also seen in people with muscle weakness in one direction due to stroke, or spasticity due to neurological impairments. An example of this type of muscle shortening would be a child with cerebral palsy that presents with calf muscle spasticity. These are extreme cases demonstrating the effect of muscle imbalances, but a similar mechanism may be at work in the average person that sits at the desk the majority of the day. Maybe sitting results in an overactive psoas which in combination with weak glutes can produce a similar effect.

Stretch It Out?

So if sitting really does cause a problem for our hip flexors, what is the best way to go about restoring flexibility? Muscle lengthening due to stretching is thought to occur via the same mechanisms as shortening, but in reverse. When a muscle is held under tension the tissue can form new sarcomeres (or links in the chain) to add length. There may also be neurophysiologic mechanisms involved, where the central nervous system responds to stretching by allowing increased extensibility of the muscle tissue.

The big questions are how much and what way of stretching counteract the effects of sitting for several hours or more per day?

Both human and animal trials have been conducted to determine the amount of time needed to prevent muscle shortening and the time periods range from as little as 30 minutes to as much as six hours a day to prevent adaptive shortening of the muscle tissue. No studies have been done looking specifically at sitting but it’s probably safe to assume that anyone spending a good part of their day seated should invest a small part of each day engaging in activities the promote hip extension.

From a purely biomechanical perspective, passive stretches like the one displayed in the picture can be employed to attempt to lengthen the hip flexors. While I think static stretching has its place, it also has limitations in that it ignores the potential neurophysiological and muscle strength contributions to the issue. For a more complete approach, dynamic stretches that cause hip extension should be included as well as specific exercises for glute strengthening to increase the ability of the gluteus maximus to create torque at the hip. Some examples would be:

- Prone hip extension: lying on your stomach and kicking the leg up into air with either the knee straight or bent

- Standing hip extension: Kicking the leg behind you, similar to prone extension except in standing

- Deep squatting

- Lunges

Since tight hip flexors are just one of the hazards associated with sitting, another option is to look for ways to decrease the amount of time we spend each day perched on a chair. Standing, squatting, lying down, and even sitting on the floor are all viable (and arguably better) alternatives that prevent the body from getting too well adapted to any one static position.

Summary

Sitting may cause the hip flexors to lose range of motion or feel stiff, but the underlying mechanism driving that change may be more complicated than a simple change in the physical length of the muscle itself. Anyone looking to avoid adaptations in the body associated with prolonged sitting would probably should engage in activities using the opposite motions and positions to sitting.

Keys To Good Squat Form

- Hips Back

Sit back into the squat. Try to push your butt back as you lower yourself down. The squat should look similar to the motion of sitting down in a chair. To do this, you need to keep your weight back on your heels and keep your knees from traveling too far forward.

On the way up, think about pushing through your heels and driving your hips up to the sky first, before straightening the rest of your body.

- Knees Out

Keep your knees moving in the direction of your feet. Don’t let the knees move closer together as you squat. It may help to think of driving your knees apart as a way to keep them from collapsing in.

- Good Depth

Try to get your thighs at least to parallel with the ground. This may be hard to do if you’re just starting out. At first, only lower yourself down as far as you feel comfortable while trying to maintain good form. Gradually as your strength and flexibility improves it will become easier to go lower.

- Chest Up

The lower you go in the squat, the more the lower back tends to start rounding. This is especially true if you have tightness in your hamstrings or upper back. Keeping you chest up and shoulders pulled back is a good way to maintain the natural arch in your lower back.

Happy Squatting!

Application of Passive Stretch and Its Implications for Muscle Fibers

+ Author Affiliations

1. PG De Deyne, PT, PhD, is Assistant Professor, Departments of Orthopaedic Surgery, Physiology, and Physical Therapy, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md. Address all correspondence to Dr De Deyne at Department of Orthopedics, University of Maryland School of Medicine, MSTF, Room 400, 10 S Pine St, Baltimore, MD 21201 (USA) (pdedeyne@smail.umaryland.edu)

To increase range of motion, physical therapists frequently use passive stretch as a means of gaining increased excursion around a joint. In addition to clinical studies showing effectiveness, thereby supporting evidence-based practice, the basic sciences can explain how a technique might work once it is known to be effective. The goal of this article is to review the potential cellular events that may occur when muscle fibers are stretched passively. A biomechanical example of passive stretch applied to the ankle is used to provide a means to discuss passive stretch at the cellular and molecular levels. The implications of passive stretch on muscle fibers and the related connective tissue are discussed with respect to tissue biomechanics. Emphasis is placed on structures that are potentially involved in the sensing and signal transduction of stretch, and the mechanisms that may result in myofibrillogenesis are explored.

Physical therapy interventions often are used to restore normal mobility, and physical therapists use a variety of techniques, such as passive range of motion, stretching by the therapist or by the patient, splinting, and serial casting.5,7–11 Underlying these approaches appears to be a belief that longer muscles (including muscle fibers and the related connective tissue) will have greater excursion ability; thus, there will be increased range of motion around the joint, especially if any shortened periarticular tissues are also stretched.12,13

Figure 1.

Medial view of the ankle. This example shows the application of passive stretch to the human ankle. A passive force of 100 N is applied 150 mm from the joint center, and the ankle is moved through an arc of 30 degrees. The Achilles tendon and soleus muscle fascicles are stretched according to the anatomic architecture (α=pinnation angle, a and b=moment arms, F1=stretch force, F2=reaction force at the Achilles tendon).

If you want to alter your body composition, you cannot overlook exercise. However, some forms of exercise are clearly more effective than others in this regard.

Most people who exercise are still focusing on slow endurance-type exercises, such as running on a treadmill, which is not only time consuming but ineffective as well—especially for weight loss.

When it comes to shedding unwanted pounds and reworking your fat-to-muscle ratio, high intensity interval training (HIIT) combined with intermittent fasting is a winning combination that I don’t think can be beat.

The HIIT approach I personally use and recommend is the Peak Fitness method, which consists of 30 seconds of maximum effort followed by 90 seconds of recuperation, for a total of eight repetitions.

I also recommend incorporating Buteyko breathing, which involves breathing only though your nose while working out. This raises the challenge to another level.

Intermittent fasting involves cutting calories in whole or in part, either a couple of days a week, every other day, or even daily as in the case of the scheduled eating regimen I recommend for those with insulin resistance (overweight, high blood pressure, diabetes, or taking statin drugs).

When you combine these two strategies, especially if you exercise in a fasted state, it effectively forces your body to shed fat because your body’s fat burning processes are activated by exercise and lack of food.

HIIT Trumps Conventional Cardio for Fat Loss, Calorie Burning, and More

The featured article in The Leader1 discusses the many advantages of high-intensity interval training over conventional cardio, including the following five—all of which have sound scientific support:

- Maximized calorie burn. As noted in the featured article, “HIIT workouts burn more calories than traditional workouts, especially after the workout.

The two-hour period following a workout is referred to as EPOC (excess postexercise oxygen consumption), and it’s when the body works to restore itself to pre-workout levels, in turn using more energy.”

The American College of Sports Medicine2 recommends 20 minutes of more vigorous activity three days per week, noting that HIIT workouts tend to burn an extra 6-15 percent more calories compared to other workouts, thanks to the calories you burn after your exercise.

- Optimized fat burn. HIIT also burns more body fat in less time.

- Improved cardiovascular health. Contrary to conventional thought, HIIT is actually more efficient when it comes to improving your cardiovascular and heart health compared to long and slow endurance-type cardio.

According to the featured article: “In a recent 2014 study… vigorous HIIT-style workouts helped heart transplant patients keep their blood pressure levels in check better than moderate intensity exercise. This research suggests that high-intensity exercise might be a safe and efficient way to manage blood pressure in the long-term.”

- Greater endurance, speed, and performance. While it seems reasonable to assume that improved endurance goes hand in hand with longer workouts, this actually isn’t necessary. HIIT can dramatically cut the time required by engaging both your aerobic and anaerobic systems.

As explained in the featured article: “During high-intensity surges, you’re supposed to go all-out—until you reach that breathless, ‘OMG-I-can’t-take-this-anymore’ feeling.

When you feel as though your heart is about to pound out of your chest, it’s a sign you’ve crossed over into the anaerobic zone. Pushing yourself like this can help you become stronger and fitter over time.”

In one study,3 recreational cyclists were able to double their endurance capacity in just two weeks by doing three sessions of sprint interval training per week!

- Optimal efficiency. One of the real boons of HIIT is the fact that you can complete an entire workout in a total of 20 minutes. And the fitter you get, the less frequently you need to do them.

High intensity exercises also cuts down on the time required to notice fitness results. According to research presented at the American College of Sports Medicine Annual Meeting in 2011, just two weeks of HIIT can improve your aerobic capacity as much as doing endurance training for six to eight weeks.

Besides these advantages, other benefits associated with high intensity interval training include:

- Improved muscle tone

- Higher energy levels

- Boosted sex drive

- Optimized production of human growth hormone (HGH), also known as “the fitness hormone,” which is important for strength, health and longevity

- Increased production of testosterone

Intermittent Fasting May Be the Best Way to Shed Excess Fat

While high intensity interval training is the best exercise to shed fat, intermittent fasting is by far the most effective way to lose weight overall. There are a few different intermittent fasting regimens, but the one I recommend for most people who are overweight, is to simply restrict your dailyeating to a specific window of time—ideally a window of eight hours or less. This means no calories at all during your non-eating window. You can have water, tea, and coffee, but no milk or sugar added.

This is one of the most aggressive intermittent fasting regimens, so you’ll likely notice results far sooner than with some other eating schedules. Best of all, despite being aggressive, it’s still really easy to comply with once your body has shifted over from burning sugar to burning fat as its primary fuel. If daily fasting sounds intimidating, keep in mind that this is not a permanent eating program.

Once your insulin resistance improves and you are normal weight you can start eating more frequently, as by then you will have reestablished your body’s ability to burn fat for fuel—that’s the key to sustained weight management. This is what happened to me. I was losing far too much weight on one meal a day and had to increase to two meals to not lose too much weight.

Moreover, if you’re hesitant to try fasting for fear you’ll be ravenously hungry all the time, you’ll be pleased to know that intermittent fasting will virtually eliminate hunger and sugar cravings. Again, it may take a few days or even weeks, but once your body shifts into burning fat for fuel rather than sugar, the sugar cravings will be a thing of the past. I’m a fellow of the American College of Nutrition and have studied nutrition for over 30 years, and I’d never personally encountered or experienced hunger cravings just disappearing like they did when I implemented intermittent fasting!

For Optimal Weight Loss Results, Also Pay Attention to What You Eat

In addition to paying attention to when you eat, it’s also important to address the quality of the food you eat. While some intermittent fasting advocates permit you to eat just about any kind of junk you want as long as you restrict calories on certain days, I believe this is really counteractive. When fasting, optimal nutrition actually becomes more important, not less so. As a general rule, to lose weight, you need to:

- Avoid sugar, processed fructose, and grains. This effectively means you must avoid most processed foods.

- Eat plenty of whole foods, ideally organic, and replace the grain carbs with:

- Large amounts of fresh organic locally grown vegetables

- Low-to-moderate amount of high-quality protein (think organically raised, pastured animals). Most Americans eat far more protein than needed for optimal health. I believe it is the rare person who really needs more than one-half gram of protein per pound of lean body mass. Those that are aggressively exercising or competing and pregnant women should have about 25 percent more, but most people rarely need more than 40-70 grams of protein a day.

| Red meat, pork, poultry, and seafood average 6-9 grams of protein per ounce.

An ideal amount for most people would be a 3-ounce serving of meat or seafood (not 9- or 12-ounce steaks!), which will provide about 18-27 grams of protein |

Eggs contain about 6-8 grams of protein per egg. So an omelet made from two eggs would give you about 12-16 grams of protein.

If you add cheese, you need to calculate that protein in as well (check the label of your cheese) |

| Seeds and nuts contain on average 4-8 grams of protein per quarter cup | Cooked beans average about 7-8 grams per half cup |

| Cooked grains average 5-7 grams per cup | Most vegetables contain about 1-2 grams of protein per ounce |

- As much high-quality healthful fat as you want (saturated and monounsaturated from animal and tropical oil sources). Most people need upwards of 50-85 percent fats in their diet for optimal health—a far cry from the 10 percent currently recommended. Sources of healthful fats to add to your diet include:

| Avocados | Butter made from raw grass-fed organic milk | Raw dairy | Organic pastured egg yolks |

| Coconuts and coconut oil | Unheated organic nut oils | Raw nuts, such as almonds, pecans, and macadamia, and seeds | Grass-fed meats |

Intermittent Fasting and High Intensity Exercise Is a Winning Combo for Weight Loss

If you’re like most Americans you probably have a few unnecessary pounds you’d prefer to get rid of. Intermittent fasting is by far the most effective strategy I’ve found for shedding excess weight, and when it comes to exercise, high intensity exercises are the most efficient. In combination, these two strategies can quite literally reshape your body and life.

My only caveat is that you also need to pay attention to the quality of the food you eat—intermittent fasting is not a ticket to eating McDonald’s… Since both HIIT and intermittent fasting help shift your body from burning sugar to burning fat as its primary fuel, it’s important to feed your body the right nutrients. Out with the sugar, and in with the healthy fats! Making these dietary shifts, and adding two or three weekly sessions of high intensity exercises is, I believe, a solid strategy for reaching your weight loss and fitness goals.

Shoulder problems and solutions

How many times have we done or seen people at the gym doing the “wind-mill” stretch before a workout? Sooner or later every weightlifter will experience pain and tenderness in their shoulder. The pain usually lingers for weeks if not months, and the pain is usually more noticeable when performing a bench and/or overhead press, but it gets better later into the workout. Chances are someone has said that it is possibly bursitis or rotator cuff issue, and rest and “take it easy” is the best way to treat it, but taking it easy or rest isn’t going to happen.

Most of the time when someone comes into my office with shoulder pain, it is caused by impingement syndrome. Impingement syndrome occurs when the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles become irritated and inflame as they pass through the subacromial space. This results in pain, weakness, and loss of movement at the shoulder joint1. Some of the causes are2:

- Keeping the arm in the same position for a long period of time.

• Sleeping on the same arm each night.

• Overhead sports like tennis, baseball (especially pitching), swimming, and weight lifting.

• Overhead jobs like painters.

• Poor control or instability of the shoulder muscles.

Early on the pain usually only happens with overhead activities and lifting the arm. Over time, the pain may start happening at night, especially when laying on the involved side. Pain is usually located in the front of the shoulder and may radiate to the side of the arm. If the pain radiates past the elbow, it might be due to a pinched nerve. The best way to diagnose impingement is through history and orthopedic testing. Some of the details that should be made available to your doctor when evaluating possible shoulder impingement include any history of previous trauma, positions that aggravate the pain, and what makes it better or worse. Another important factor to consider is how it affects your daily activities and workouts. What exercises are the worst to perform? Do you train your other muscles of the shoulder? If so, how often? Answering these questions will help your doctor to provide the correct diagnosis and the best course of action.

If you are suffering from impingement of the shoulder, the best thing to do is to rest, and stop all activities that will aggravate the shoulder.

A stretching program should also be implemented to increase flexibility. Stretching should include the posterior shoulder, the pectoralis minor, triceps, and biceps. The Sleeper Stretch is an excellent stretch for impingement.

Sleeper Stretch

When performing a sleeper stretch, make sure that you are not laying flat on your scapula, you want to lay mostly on your rib cage and the outside border of your scapula. Your arm should be 90 degrees from your torso with the palm of your hand facing the ground. Then you want to gently push down at your wrist until you feel a mild stretch on your posterior shoulder and hold for 30 seconds. Do this for about 3 reps. You should not feel anything in the front of your shoulder, and be careful to not push too hard. With this stretch your hand is not supposed to touch the ground. The goal is to feel a mild stretch in the back of the shoulder and hold the position4.

Rest and avoid overhead workouts are the best way to treat impingement syndrome, along with regular stretching, and myofascial release techniques the symptoms should alleviate sooner. Remember, if you are experiencing pain, seek the help of a health care specialist; it won’t just “go away”.

Psoas

I was delighted when I first came across Liz Koch’s amazing work because it confirmed much of what I’d been intuiting on my own. I had begun to open and close my yoga practise with hip opening poses with the specific intention of releasing tension in my psoas and hip flexors. I’d breathe and imagine tension flowing out of constricted muscles to be released as energy into the torso.

It worked, I’d feel my body soften yet somehow grow stronger.

Reading Liz Koch I instantly realized what I was doing – by learning to relax my psoas I was literally energizing my deepest core by reconnecting with the powerful energy of the earth. According to Koch, the psoas is far more than a core stabilizing muscle; it is an organ of perception composed of bio-intelligent tissue and “literally embodies our deepest urge for survival, and more profoundly, our elemental desire to flourish.”

Well, I just had to learn more. Here is just a sprinkling of the research that Liz Koch and others have uncovered regarding the importance of the psoas to our health, vitality and emotional well-being.

The Psoas muscle (pronounced so-as) is the deepest muscle of the human body affecting our structural balance, muscular integrity, flexibility, strength, range of motion, joint mobility, and organ functioning.

Growing out of both sides of the spine, the psoas spans laterally from the 12th thoracic vertebrae (T12) to each of the 5 lumbar vertebrae. From there it flows down through the abdominal core, the pelvis, to attach to the top of the femur (thigh) bone.

The Psoas is the only ‘muscle’ to connect the spine to the legs. It is responsible for holding us upright, and allows us to lift our legs in order to walk. A healthily functioning psoas stabilizes the spine and provides support through the trunk, forming a shelf for the vital organs of the abdominal core.

The psoas is connected to the diaphragm through connective tissue or fascia which affects both our breath and fear reflex. This is because the psoas is directly linked to the re ptilian brain, the most ancient interior part of the brain stem and spinal cord. As Koch writes “Long before the spoken word or the organizing capacity of the cortex developed, the reptilian brain, known for its survival instincts, maintained our essential core functioning.”

Koch believes that our fast paced modern lifestyle (which runs on the adrenaline of our sympathetic nervous system) chronically triggers and tightens the psoas – making it literally ready to run or fight. The psoas helps you to spring into action – or curl you up into a protective ball.

If we constantly contract the psoas to due to stress or tension , the muscle eventually begins to shorten leading to a host of painful conditions including low back pain, sacroiliac pain, sciatica, disc problems, spondylolysis, scoliosis, hip degeneration, knee pain, menstruation pain, infertility, and digestive problems.

A tight psoas not only creates structural problems, it constricts the organs, puts pressure on nerves, interferes with the movement of fluids, and impairs diaphragmatic breathing.

In fact, “The psoas is so intimately involved in such basic physical and emotional reactions, that a chronically tightened psoas continually signals your body that you’re in danger, eventually exhausting the adrenal glands and depleting the immune system.”

And according to Koch, this situation is exacerbated by many things in our modern lifestyle, from car seats to constrictive clothing, from chairs to shoes that distort our posture, curtail our natural movements and further constrict our psoas.

Koch believes the first step in cultivating a healthy psoas is to release unnecessary tension. But “to work with the psoas is not to try to control the muscle, but to cultivate the awareness necessary for sensing its messages. This involves making a conscious choice to become somatically aware.”

A relaxed psoas is the mark of play and creative expression. Instead of the contracted psoas, ready to run or fight, the relaxed and released psoas is ready instead to lengthen and open, to dance. In many yoga poses (like tree) the thighs can’t fully rotate outward unless the psoas releases. A released psoas allows the front of the thighs to lengthen and the leg to move independently from the pelvis, enhancing and deepening the lift of the entire torso and heart.

Koch believes that by cultivating a healthy psoas, we can rekindle our body’s vital energies by learning to reconnect with the life force of the universe. Within the Taoist tradition the psoas is spoken of as the seat or muscle of the soul, and sur rounds the lower “Dan tien” a major energy center of body. A flexible and strong psoas grounds us and allows subtle energies to flow through the bones, muscles and joints.

Koch writes “The psoas, by conducting energy, grounds us to the earth, just as a grounding wire prevents shocks and eliminates static on a radio. Freed and grounded, the spine can awaken”…“ As gravitational flows transfer weight through bones, tissue, and muscle, into the earth, the earth rebounds, flowing back up the legs and spine, energizing, coordinating and animating posture, movement and expression. It is an uninterrupted conversation between self, earth, and cosmos.”

So, it might be worth it, next time you practice, to tune in and pay attention to what your bio-intelligent psoas has to say.